Keval Singh

It seems he died while napping in the late afternoon. He was just weeks away from his thirty-fifth birthday. No one could understand why someone so full of promise and ambition could slip away just like that. But such is the work of God.

Relatives began gathering at his house since late the next morning. Those living close by were the first to arrive. Dressed modestly in black or white, they shuffled their feet toward the open gate of the fifth floor flat. One by one, they entered, and fell into the lap of his mother, who sat on the edge of the light brown sofa. They wailed, howled, but his mother sat there virtually motionless. Arjun was the more irritable one. These were relatives they never heard from unless someone needed help of some sort, or it were Diwali. He pried them away from his mother. No point having her salwar kameez ruined by their fake tears.

Arjun’s sister Neeta watched the drama from the mouth of the corridor leading to their bedrooms. She knew what was running through her relatives’ minds, only because she’s heard them verbalize their concerns before. Some years earlier, at the funeral of her eldest aunt, she overheard a conversation between two relatives – one distant, and one particularly immediate:

‘Who will get the house?’

‘She got married just weeks ago. I’m not sure if she wanted her husband to get it. Otherwise it’ll be my youngest sister.’

‘Oh? Where’s her husband?’

‘He’s here,’ she gestured to the row of benches behind.

‘Why not here with the rest of you? By the way, I don’t mean to be rude or anything, but is he Pakistani?’

Their brother Karan had died single. But such questions were still relevant.

In his bedroom, for example.

The books standing against one another on the black bookshelf were abuzz with – for lack of a better word – excitement. Some were relieved that they would get to move out. Karan never read a book more than once. And those in his collection felt trapped, having to stand around collecting dust which he would wipe off once every few months. For the most part however, the mood was one of trepidation. Their future was uncertain.

Most of them were works of fiction that Karan had picked up since he was 21. There were at least 160 books spread out in 10 cubbyholes of the bookshelf. Most were neatly arranged vertically; two rows in each cubby, with his favourites facing out. A lack of space on the shelf meant some books were stacked horizontally on top of others. There would have been more, but Karan often borrowed books from the library. Sometimes he regretted doing this, especially when a book that had to be returned after two weeks would have looked better as a permanent entity in his library.

‘I don’t think they’re going to keep us,’ one thin collection of Pakistani short stories said.

‘ I don’t think they’ll keep you,’ said a 700-page novel confidently.

‘And you think you’re so special?’

‘Well I am one of his favourite books. He tried getting both Neeta and Arjun to read me.’

‘But they didn’t,’ came the triumphant reply. ‘Plus, your spine’s in such a bad shape. Karan obviously didn’t take very good care of his favourite book.’

‘He was younger when he bought me. The boy wasn’t too concerned about creased spines at the time. And I’ll have you know that Neeta doesn’t give much attention to such things. She’d probably be more willing to save me than burden herself with maintaining the others in their near-pristine conditions.’

The other books were listening intently to this exchange. Some were murmuring among themselves, desperately seeking reassurances.

‘But Neeta never finishes books. She’s not as voracious a reader her brother was.’

Everyone looked around to find out who had spoken.

‘I’m here,’ the slim hard cover raised her voice. She was two cubby holes away from the volume of Pakistani short stories and the 700-page novel. Her story was one of tragedy from the valleys of Afghanistan.

‘Your point being..?’

‘Simple. Neeta prefers books that aren’t too thick. So we slim ones have a better chance of survival.’

‘Sure. But she doesn’t like those with heavy subjects. Remember how she took forever just to finish leafing through you?’

‘That’s because she was going through a rough period. Otherwise she had told Karan that my tragic tale intrigued her.’

‘What’s with all this talk anyway?’ the Ahmed Ali novel finally spoke up. ‘What’s this thing about being saved? Why are you spreading fear and panic?’

The 700-page novel spoke now. ‘Uncle, haven’t you heard? Karan is dead. Out there they’re going to start discussing who gets what share of his assets. We are discussing who will stay on the shelf and who will go’.

‘Why would it come to that anyway?’

‘Well Neeta and Arjun are not Karan. I don’t trust them. Arjun finds reading a bore. It wouldn’t take him much to dump us in some bin. He’d want the space for his things.’

‘Haha. You lot think too much. And you call me the old man! I think you’re still smarting from that time when Arjun refused to read you.’

‘Say what you want. You never did excite Karan much anyway..’

‘What’s that supposed to mean? Do you know how thrilled he was when he found me sitting idle in a bookshop in Delhi? You should have seen his eyes and the look on his face! It was as if the Koh-i-noor diamond had fallen into his lap!’

The Pakistani volume sniggered, ‘Yea but he’s never mentioned you since. The ‘twilight’ in your title took on an added significance it seems.’

The Ahmed Ali book struggled for a response. ‘What about Neeta? At least she tries to read.’

‘She tried to read some of us Uncle. I’m afraid despite your size, you don’t stand a chance. Let’s face it, Neeta’s not one to appreciate historical novels.’

At this point, the 700-page novel swung the focus to another group of books. ‘I’ll say the same about the travel narratives. Neeta barely goes beyond work. And if she does, it’s only to places like Bangkok to shop.’

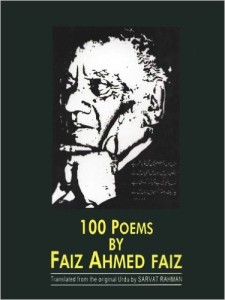

It was then that Faiz Ahmed Faiz decided to quote from one of his poems:

‘Put out the lights! Take away wine, goblet and flask!

Lock up your sleepless doors, O solitary heart

No one will come here now, no one, no one.’

That was the end of the debate. It was no use speculating. They could go back and forth to entrench their individual positions, but none of it would undo any decision the siblings would decide to take. Maybe they would be given away to friends who read? There was a slim chance they would be recycled. Karan had after all instilled that habit in them. But the thought of being reduced to fresh pages, torn apart from their tattooed words, and the words they were pressed against day-in and day-out, was barely any consolation. And while they contemplated their fate, some of the books wondered what would happen to all of Karan’s other possessions – his pins, movie stubs, photographs, trinkets from abroad. What would happen to all his letters, his notebooks? It’s so much easier to find new owners for clothes, shoes, bottles of perfume even.

*

The rest of the week passed slowly. The relatives took turns to stay over as part of the mourning period. Conversations slowly found their way into the flat, as did pockets of chuckles over Karan’s quirks. Sometime toward the end of the week everyone woke up to the strong smell of aloo paronthas, Karan’s favourite Punjabi breakfast. The sign was clear, so said some of the elders. That morning, the womenfolk prepared aloo paronthas for breakfast.

*

On the tenth day, a Saturday, everyone gathered at the gurudwara for prayers for Karan’s soul. There was a sizable turnout.

The siblings then began the process of taking care of Karan’s finances: the ownership of the flat, claims from his insurance policies, CPF monies, bank balances. Despite his young age, Karan had long ago decided what should go to whom. And that day when the scent of aloo paronthas filled the air, Neeta felt as if her brother had come back to remind them of what needed to be done.

But what about the books?

‘He loved them more than anything else,’ Neeta said, standing in front of the bookshelf with Arjun one morning.

‘I remember pissing him off on several occasions when I’d pull a book open so wide I would crease the spine. He would scream as if I’d removed his liver!’

Arjun managed a chuckle. ‘And when you borrowed any of his books you’d wrap them up in a cloth to prevent any damage – remember that? I can’t believe he was that anal about his books!’

‘I miss that though. He’d taken such good care of them. Some of them look like they moved in straight from the bookstore onto his shelf without ever being opened.’

‘Yea.’

Neeta sighed.

‘What do we do with them now?’

‘I really don’t know,’ Neeta scanned the bookshelf, looking at the various spines pressed against one another. The books too were waiting for a response. The tension was palpable.

‘You know I don’t read.’ Arjun concluded.

Neeta nodded imperceptibly.

‘Maybe we should have just burned them with him.’